FARMINGTON CORNER

A continuing tale of life in the boonies

No. 288

Poets who matter: 4. Robert Garioch

FARMINGTON - As mentioned last week, the bureaucratic portcullis has been lowered and application forms to be Poet Laureate of Rochester, New Hampshire, USA, The World, are no longer obtainable. Mayor Walter Hoerman is now processing the resumes of several P.L. wannabees and will announce his choice at the November City Council meeting.

It gives little time in which to lure public curiosity away from the mudslinging of this fall’s municipal election campaign and onto poesy’s loftier plane. One can but try.

This week’s man of verse, Robert Garioch, is hardly known beyond his native country, perhaps because he wrote in Lallans, the Scots language still spoken by peasants in private and poets in public.

Yet Garioch it is, despite him being an Edinburgh man, who wrote:

"In Glesca and in Hell, muckle is kent of reik and flames … ."

Much is known of smoke and flames, indeed.

Blackhill, the Glasgow (or Glesca) district where I worked as a policeman in the 1970s, was a kind of hell, the ingenious creation of Glasgow’s post-World War II public housing managers as an awful god-like warning to troublesome public housing tenants in other areas of the city to behave or be banished there.

* * *

Garioch, appreciating the common man and his travails, translated many of the 19th century sonnets of Italian vernacular poet Giuseppe Belli into Lallans, and one is The Puir Thief, containing these lines of a prisoner addressing a magistrate:

I am a thief, I ken, and I think shame

but still ye hae a duty to find out

if hunger or my badness is to blame.

This poem, and another of Garioch’s works, Sisyphus – the Greek legend brilliantly converted into Lallans - remind me of the time when I helped some local tenants establish a youth club in Blackhill.

"There’s nothing for the weans to do in Blackhill," was the truthful cry of many a parent whenever their teenager landed foul of the law – and this pointed to the need for a football team. But a football team needed a football strip (uniform) before they could join a league, and a football strip needed money - in short supply in Blackhill.

Around 1935, when Blackhill was built, the city fathers had erected sturdy iron railings around every garden, and in the early 1940s, to impress upon everyone that sacrifice was needed to beat Hitler, council workmen had been sent to cut them all down again with acetylene torches. Mountains of iron railings were carted away to be melted into guns for fighting the Hun, but rusted instead, in a municipal scrap yard. And 30 years later, Blackhill still had no fences and very sparse flora.

On Queenslie Street, though, cowering hard against the building and straggling up a rone pipe, was a miracle of Nature, a rambling rose. I was aware of it because the lady living in the ground apartment of the block loved the plant, and often called the police to intervene on its behalf against packs of marauding dogs and children.

"You need a fence, missus," I told her, with football club fund-raising in mind, and she agreed that £3 (about $5) was a fair price.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JOHN NOLAN

Acrehill Street, Blackhill, Glasgow, c. 1972

It's Anarchy we want, Anarchy.

End all the criminal courts, cells, the Dock ...

- Robert Garioch, Speech

With the demise of Cowlairs heavy engineering works, the nearby Springburn area of the city was in decline and shops were being demolished, so the Northern Division’s police Landrover was pressed into service one June night in 1972 to bring over a few loads of wooden shelving. The Oswald boys banged up a fence the next morning, and while it protected the rose and the woman was quite pleased, the construction was a visual monstrosity. Daylight revealed what darkness had not – the shelves were of many hues, yellow, pink, sky blue and cream, and the Oswalds were not carpenters.

By nightfall, the fence was the talk of the police station.

"It’s more like an elephant stockade. Ye ought to call Queenslie Street a safari park and charge a pound to drive along," suggested a sergeant, before slumping down for a nap.

* * *

There had to be an easier way. Beyond Blackhill, running towards the city boundary, were long fields of rhubarb (barely worth stealing) and beyond the rhubarb were the mushroom sheds of a dying enterprise. After a phone call of explanation, the farmer donated a few hundreds wooden slats from mushroom boxes he no longer would use to the football strip cause, and the Landrover once again ferried the fencing material into Blackhill.

This time, Willie Jamieson, a Craigendmuir Street tenant with a great spirit and a bad heart that kept him on pills and medicine, took delivery of the slats, and over the course of the next few nights, fence posts were "borrowed" from the many derelicts sites that pockmarked northeast Glasgow.

Willie enlisted his neighbors, the Lindsays, which caused police brows to furrow, for these characters had once been officially charged with "theft of one dwelling house." It turned out, though, that John and Tam Lindsay were keen to be youth club football managers, and as they pointed out, it was only half a house, a partly dismantled municipal prefab, that they had unsuccessfully made off with at three miles an hour on a horse and cart.

So, with the Lindsays’ help, Willie’s garden fence was quickly constructed first, and that became the storage yard for the many piles of mushroom slats that were the perfect size for fence palings.

I came on duty at 7 a.m. the next day, ready to act as fence salesman and treasurer of the Blackhill Wolves Youth Club. But walking down to Willie’s house from the police station, I was met with glum faces – all the fence slats had been stolen during the night. It was back to Square 1.

Sisyphus, you may recall, was condemned by the Gods to spend eternity manhandling a heavy boulder up a hill. When it reached the summit, his burden would hurtle back down, and Sisyphus would have to descend and start his toil all over again.

Garioch, using classic Greek meter, translated the legend into Lallans, while wryly drawing a parallel between boulder-trundling and the repetitious drudgery of 20th century working conditions.

"Bumpity doun in the corrie gaed whuddran the pitiless whun stane …" thought I, dismally seeing the applicability of Garioch’s opening line to the present setback.

* * *

The first commandment of Blackhill society was Thou Shalt Not Grass, meaning that no matter how heinous the crime, no one should pass on any information to the police. But Blackhill people also loved "weans" and the thief had erred by stealing the means to buying their football strips, placing the housing project in a deep moral dilemma.

Around lunchtime, a small boy was sent into the police station to say that the stolen fencing might be in an attic of the six-apartment block at 17 Craigendmuir Street – just round the corner from where it had been stored. Constable Gilbert Hill, a rawboned, good-natured police officer, went with me to follow up on Blackhill’s first ever crime tip.

The passage leading to the common stairway of Glasgow tenement houses is called a close, and as we entered the close at 17 Craigendmuir Street, out of habit, we both glanced up at the electrical fuse box that served the six apartments.

It was rare for all six South of Scotland Electricity Board official fuses to be present in a Blackhill close – there were always one or two families whose power had been cut off by fuse removal because of non-payment of a bill, even although this was more attributable to their home electricity meters being robbed of their shillings by ubiquitous burglars than to sloppy budgeting. To overcome this hardship people surreptitiously tapped their wiring into other circuits or reinserted dangerous do-it-yourself aluminum foil fuses to restore electricity, illegally.

Policemen, out of laziness or sympathy, usually turned a blind eye to fuse box tampering unless formally contacted by the SSEB or officious police inspectors.

"Just one fuse missing in this close," Gilbert observed, before we bounded up the stairs to the top landing on the trail of the fence.

The trapdoor leading to the building’s attic had no padlock and looked like it should simply flap open. I rapped on one of the landing’s two doors to borrow the chair we needed to stand on. No reply. Gilbert banged the other and a meek woman looked out, and then handed us a rickety chair without being asked.

Mounting the chair, Gilbert pushed on the trapdoor, which remained solidly shut. The only thing rising was our ire.

I shot downstairs, went into the back court and came back with a large wooden clothes pole that we used as a battering ram against the trap door. With a great splintering noise, the entryway was breached and we clambered into the attic.

Normally, care must be taken in attics (usually during searches for stolen goods) to avoid stepping between the joists and putting a foot through someone’s plaster ceiling below. But this entire attic was neatly floored with wooden mushroom box slats that had recently, very recently, been tacked into place. Daylight streamed in through a skylight that was propped open, allowing a telescope on a tripod an unimpeded field of vision all the way over to Provan Gas Works. The attic, it dawned on us, was being converted into a pigeon loft by one of those Blackhill hobbyists who passed long weeks without employment by racing pigeons. Not using the football team’s only means of buying shirts and pants, though.

The puzzle remained, how had this pigeon fancier, who must have labored all night, got out of the attic after boarding over the trap door?

The answer came quickly. In a corner of the attic, we saw light coming up from below, and found that a neat hole had been cut in the ceiling of the house I had first sought a chair from. A ladder led down into a livingroom, but before descending we called down through the hole.

No reply – and then the house was suddenly plunged into darkness.

"Somebody’s pulled the fuse in the close," said Gilbert, diving down the ladder and opening the apartment’s front door onto the landing, upon finding the house empty.

A check on the communal fuse box showed five fuses now missing, as the tenants of 17 Craigendmuir Street scrambled into low profile mode, and a radio call to the Electricity Board confirmed that only one home was the legal recipient of power – the lady who loaned us the chair.

Gilbert and I settled on the charges to bring against the pigeon racer – theft of fencing materials, malicious mischief to Glasgow Corporation property by cutting a hole in a ceiling, and stealing electricity.

We decided to ignore the illegal connections of the other tenants, but suspicion of the law was deeply ingrained, and no-one showed themselves as we waited beside the fuse box for the arrival of an SSEB employee from downtown Glasgow to confirm the theft of one therm of electricity by top flat right.

After half an hour, though, the window of a middle floor flat was suddenly opened and a desperate man, face wreathed in concern, leaned over and yelled, "Hey, polis. Are ye gaun tae f--- off? My tropical fish are dying."

"So eat them wi’ chips," I wrathfully shot back – a heartless remark I have often regretted, and apologize for, here and now.

As Giuseppe Belli and Robert Garioch understood, man’s transgressions are not always rooted in "badness."

The power company official arrived soon after, authenticated the offence of the top flat tenant, and we moved off, hopefully allowing the fish lover to plug his electric fuse back in and reheat his aquarium water.

Next day, the pigeon fancier came to the station to be charged with vandalism and theft of a unit of electricity, but as he had returned the fencing to the Lindsays, that part of the matter was dropped.

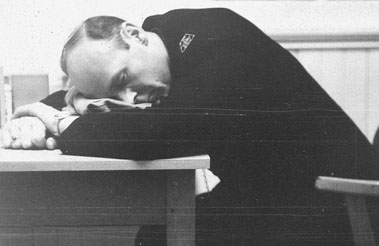

Blackhill Police Constable Gilbert Hill, the case of the

missing mushroom box slats solved, settles down for a nap.

...streikit his length on the chuckie-stanes, houpan the Boss wadna spy him ...

(stretched his length on the ground, hoping the Boss wouldn't spot him)

- Robert Garioch, Sisyphus

After this, the sun shone in Blackhill, figuratively and literally. Garden fences became the rage, and over a three-week spell of delightfully dry weather, 18 were built from the mushroom box slats, bringing in £54 (in dribs and drabs) and enabling the purchase of two complete sets of youth football strips from Lumleys of Sauchiehall Street.

And then came a night of calamitous rain, and the mushroom slats all warped and fell off their fence rails in neat rows onto the sidewalks, like leaves on a frosty morning. Aw, naw!

"Bumpity doun in the corrie gaed whuddran the pitiless whun stane …"

Sept. 21, 2003